In Memory of a Vanished Cloud, Jael Arazi

June 2023

Gabriele Picco, In Loving Memory of a Vanished Cloud, 2018-2022. Courtesy the artist

«I am a construction. A collection of experiences held together by a fragile vessel, always at risk of shattering, of the contents spilling over creating something new altogether.»1

It took a while to surrender to the necessity of replacing my phone with a new one, one more recent, with more storage space and increased functionality, better performance, nicer design. Bigger, better, faster. I waited until the very last moment I could, until my phone eventually stopped performing even its most basic function – calling – and it was as useful as a coaster.

I liked my old phone. I used it for so many years – seven! It had been through many adventures with me, a witness to trauma and healing and happiness. We shared so many memories, stored in the form of text, in archived chats and notes, or images with grainy textures that made the experiences they framed look so much cooler. I liked that it was small, at least compared to the new models. In a way, making it last for so long made me feel special. Programmed obsolescence couldn’t stop us – until it did.

I bought my new phone, choosing refurbished and not the newest model available. For some reason, a brand new, straight-out-of-the factory phone would have made it worse. I just wanted a good-enough device that could properly work, store data and execute software updates. When I received it, I was upset and left the box untouched, waiting in a corner of the living room table for a few days while I stood on the old phone’s deathbed. Finally, it exhaled its last breath without a single byte of memory left for a backup.

I decided I didn’t care. I turned the new phone on, feeling proud of myself for not experiencing any sort of attachment to past conversations and media from group chats dating back to 2013, or to the data stored in the very few apps that the elderly phone could still accommodate. The phone got going, but nothing was on it. Blank. Empty. All of a sudden my pride was overturned by a sense of loss. I felt displaced and alone. I felt anger and hatred bubbling inside of me. I took it on myself for being stupid and disregarding the risk of not doing a backup until it was too late. I blamed the old phone for being old and on the new one for being new. I wanted to smash it, destroy it, cancel its existence. I couldn’t stand the thought of seeing all my digital memories gone like that, in a matter of a few taps and pressed buttons, destroyed, their existence cancelled.

What happened to me? How could I lose control over a backup that was never made? Was that backup so important, so necessary after all? The strong emotional reaction I had was perhaps connected to what I thought I lost: seven years of my life. For seven years, every single day, I generated data and kept it in that phone, or in other forms of a digital archive. I produced memories, a testimony of my existence. Those pictures, videos, conversations, travel routes, research, my period record on the health app, all these bits of data witnessed my daily life and could show me how I’d changed, grown, and lived for seven years.

Digital archives contain our whole existence and we rely upon them to keep our memory and the memory of us intact forever, often forgetting that any kind of object that can hold something else is inherently limited. All containers, tanks, jars, boxes, vessels, even the Cloud, have a maximum capacity.

The author’s dead phone.

The unbearable physicality of the Cloud.

Improved technology has allowed us to move our entire lives through the digital dimension. We can think, read, talk, meet, love, hate, resist, through the virtual. Technology is supposed to make our life easier, simpler in its everyday activities. We don’t have to labour with our hands as much as before, e.g. for material production, and we don’t even have to use our brains anymore! Anything a human can do, a technological device, a software, an artificial intelligence will do instead.

It is the same with remembering. The whole «memorisation apparatus» dropped significantly since the advent of technology and people slowly let go of all those little habits that would help with remembering important information. We are so used to this system that most people don’t even make the effort to memorise their phone number anymore.2 Moreover, it has clearly become impossible to pick what is worth remembering out of the tonnes of information we are bombarded with at all times. Of course, memory has not always been exclusive to the mind, and the existence of archives goes a long way, but again, they have always been intrinsically limited. Paper and ink resources to write documents aren’t endless. Storage is restricted by physical space and volume. The time to produce and organise an archive depends on human productivity. This link to human rhythms and possibilities made archiving an organic process. Then, came the Cloud with its aura of limitlessness. A smokescreen diffusing the impression of a «formless cyberspace»,3 reassuring that our memories and our digital lives are in safe hands, while they are, in fact, not.

Partially thanks to its name, users understand the Cloud to be invisible, unshaped, mutating in perpetuity. It is just an informational haze flowing in the wider ecosystem of network society – or, to be more accurate, platform society4 – populated by «a circuit of electronic exchanges».5 These constitute our existence on- and offline, our digital footprints. Credit card transaction records, for example, document our activities, our needs and desires, easily retrievable at any moment. We often don’t think about the permanence of information like this, readily available not just to private users, but to governments and the companies that store it. The Cloud is drenched in power games.

It’s easy to forget the physical infrastructure that allows the Cloud to exist and operate and its legal and jurisdictional implications. Data centres are huge buildings situated in undisclosed locations, big boxes of information actually made of «copper wires, fibreoptic cables, and the specialised routers and switches that direct information from place to place».6 The paradoxical condition of the Cloud makes this ethereal aggregate of information dependent from the least ethereal of things: matter itself. Its immense retrieval capabilities rest on a series of physical limits, requiring a precise geography, territories large enough to host data centres and their servers, and giant infrastructure:

[The Cloud] presupposes redundant power grids, water supplies, high-volume, high-fiber-optic connectivity, and other advanced infrastructure. It presupposes cheap energy, as the cloud’s vast exhaust violates even the most lax of environmental rules. While data in the cloud might seem placeless and omnipresent, precisely for this reason, the infrastructure safeguarding its permanent availability is monstrous in size and scope.7

Any piece of information that appears and travels through the Cloud does not belong to the person who produced it. This seemingly infinite virtual container is in fact handled by a handful of corporations. Private companies, mostly registered in the US, are the owners of our data. A legal vacuum arose from the difficulties of territorialising the Internet. When the virtual dimension is unhinged from a specific geographic location, corporate and state powers infiltrate and establish a ‘super-jurisdiction’ that makes everyone’s data, regardless of where it was generated, subject to – again, mostly US – national laws. All dot-com, dot-net and dot-org domain names and therefore all data connected to these domains, active anywhere on Earth, fall under US jurisdiction. In the same way, all data stored by US companies in data centres abroad is subject to the 2001 Patriot Act, an anti-terrorism law that made citizens’ – all citizens’ – private information easily retrievable by US law enforcement. The US constitutes the most obvious example of this, because of this specific act and the scope of American surveillance and intelligence services, but these kinds of legal loopholes are exercised, more or less overtly, to monitor and control users all over the world. As American author and historian James Gleick (2011) previously put it, «All traditional ideas of privacy, based on doors and locks, physical remoteness and invisibility are upended in the cloud.»8 Our informational lives might be at the mercy of a Country where we have never even set foot.

My heart pounds with excitement and anticipation imagining a dissolved Cloud. The revolution of the servers, rebelling against their informational master, allying with an exhausted nature to reach maximum storage capacity and finally self-destroy. I find it curious that a whole society developed around the drive to continuous expansion is so entrapped in physical resources and buildings, always at risk of being destroyed. Is this what the apocalypse looks like?

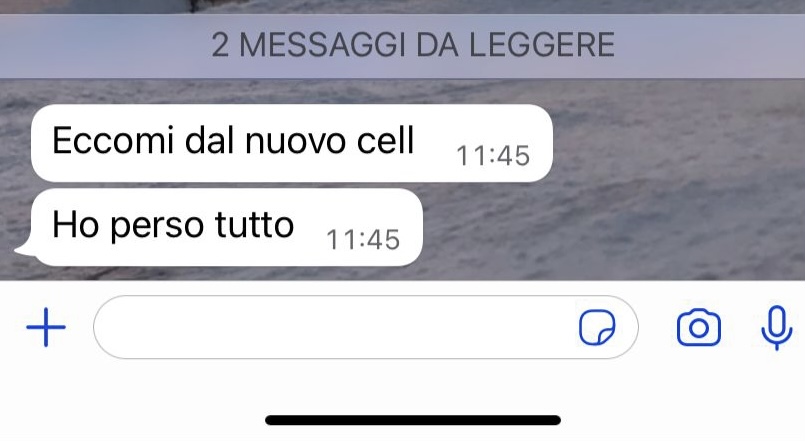

The first texts sent from the new phone. Translation: ‘here I am from the new phone. I lost everything.’ Courtesy the author

The first texts sent from the new phone. Translation: ‘here I am from the new phone. I lost everything.’ Courtesy the author«People are real. Clouds aren’t.»9

How do we choose what to remember and what to forget? Which memories to store and which to let go? It seems we don’t. Nowadays we are slaves of a compulsion to save everything, to hoard memories and suggestions and hints for a future that might be. Save for later, pin, archive. More content, more data. This might just be a natural consequence of living in a post-capitalist society determined by excessive consumerism. It is the raw face of a culture of commodities pervading all aspects of our lives, even the most organic ones. It is that sense of need that strikes me, leveraging on the fear of forgoing something of the utmost importance, when in fact we usually erase from our minds everything we save in a matter of seconds.

This is only the tip of the iceberg, a wedge made for the most part of data that we produce and do not actively store away, but that will nonetheless never disappear from some data centre in some, maybe even not too remote, part of the world, ready to be used against us. It is important to distinguish between what we wish to preserve, what we believe we need to keep and the informational traces we leave behind. We are accountable for the storing of only some of these, while the rest does not really depend on a conscious choice and is the result of the inextricably digital existence we lead, like it or not. However, data is not memory, it cannot account for the complexity of our being, in the physical and virtual dimensions. Data is dry; it’s sterile, a trace, a record of our existence, but not its entirety. Memories are emotionally charged, they reflect who we are and who we want to be, they change and evolve with us. Facts and fiction can’t be distinguished in the blur of our desires. Memory’s transcendence beyond our limited existence might be what inspired the creation of the Cloud in the first place, before its colonisation by State powers and corporate greed. We are not immortal and hoping for some digital traces to live beyond us does not mean we will be alive forever.

After my little panic attack, came acceptance that all those digital ephemera were not my life. The experience of everything I thought I lost remained with me, regardless of its documentation. I believed those digital memorabilia to be a vital extension of my being, but they were, in fact, only an extension, or, to use tech-related terminology, just plug-ins. They were memories, yes, but were not my true memory. That I can still hold on to. It doesn’t belong to anyone but me. Nobody can access it without my consent, unless I agree to share what it contains.

Jael Arazi is a curator and creative practitioner based in London. Her curatorial practice is situated on the thin line between physical and digital realities, exploring their social implications and political potentials and with a focus on audiovisual artistic practices. She co-curates the multidisciplinary project In Lucid Dreams We Dance, supported by the Italian Council grant (2022), comprising a program of events and a publication on the ritualistic aspects and the sense of belonging within electronic music and the physical and relational space of the club. Since 2021, she curated experimental exhibition projects in London and an online screening program for Covideo art platform. She holds a BA in Painting and Visual Arts from NABA Milan and an MFA in Curating from Goldsmiths University.

¹ From Jake (2023) by Benjamin Freedman.

² Geert Lovink, Stuck on the Platform. Reclaiming the Internet. Amsterdam: Valiz, 2022.

³ Jack Goldsmith and Tim Wu, Who Controls the Internet?: Illusions of a Borderless World, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006

⁴ Geert Lovink, Stuck on the Platform, op. cit. Lovink argues that the network was substituted by “something” determined by hyperconnectivity, a principle of entanglement and the loss of causality online dynamics. Platforms are regulated by the value generated through interactions, dominated by a neo-feudal condition of the user, who is the producer of this value but does not own it.

⁵ Manuel Castells, The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture. Vol. I: The Rise of Network Society. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2000 (1996), p. 442.

⁶ Jack Goldsmith and Tim Wu, Who Controls the Internet? op. cit. p. 73.

⁷ Metahaven, “Captives of the Cloud. Part II,” e-flux #38, 2012.

⁸ James Gleick, The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood. New York: Pantheon Books, 2011, p. 396.

⁹ Metahaven, “Captives of the Cloud. Part III,” e-flux #50, 2013.

¹ From Jake (2023) by Benjamin Freedman.

² Geert Lovink, Stuck on the Platform. Reclaiming the Internet. Amsterdam: Valiz, 2022.

³ Jack Goldsmith and Tim Wu, Who Controls the Internet?: Illusions of a Borderless World, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006

⁴ Geert Lovink, Stuck on the Platform, op. cit. Lovink argues that the network was substituted by “something” determined by hyperconnectivity, a principle of entanglement and the loss of causality online dynamics. Platforms are regulated by the value generated through interactions, dominated by a neo-feudal condition of the user, who is the producer of this value but does not own it.

⁵ Manuel Castells, The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture. Vol. I: The Rise of Network Society. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2000 (1996), p. 442.

⁶ Jack Goldsmith and Tim Wu, Who Controls the Internet? op. cit. p. 73.

⁷ Metahaven, “Captives of the Cloud. Part II,” e-flux #38, 2012.

⁸ James Gleick, The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood. New York: Pantheon Books, 2011, p. 396.

⁹ Metahaven, “Captives of the Cloud. Part III,” e-flux #50, 2013.