Civil disobedience in extreme UV index, anonymous

December 2023

Tehran, Iran. Courtesy the author

9.30 am

I put my headscarf on when I get into the car. The car trip is only a few minutes, I think, trying to convince myself. If I remove my scarf and the driver asks me to put it back on, I might get into an argument with him, then I would cancel my ride and would have to request another one, so I would be late for my appointment. I’ve heard of some cases where drivers in order to avoid being fined, have rejected the ride if the passenger was not wearing hijab.

To distract myself, I check the news on my phone. But the first headline I read is like a slap in the face. The Morality Police is back on the streets with their full force. Well, they have been there all this time during the past ten months, I think to myself. But not like this, not this evident. I feel a throbbing pain in my head. I am so angry that I remove my headscarf in a sudden and jerky movement. The driver looks at me from the rear view mirror. I look him daringly in the eyes, waiting for him to tell me something in regard. He doesn’t say anything maybe because he knows in a few seconds we arrive at my destination. The post office is busy. Almost half of the women are not wearing hijab. The staff doesn’t make any problem except for one of them who seems to be really annoyed by having to serve bareheaded ladies! I look around to see if there are any security cameras and wonder if the head of this office hands the footage to the authorities if they are asked to. I have read that government offices are ordered not to provide services to women who don’t cover their hair.

Fortunately, the person serving me is nice and polite.

9.45 am

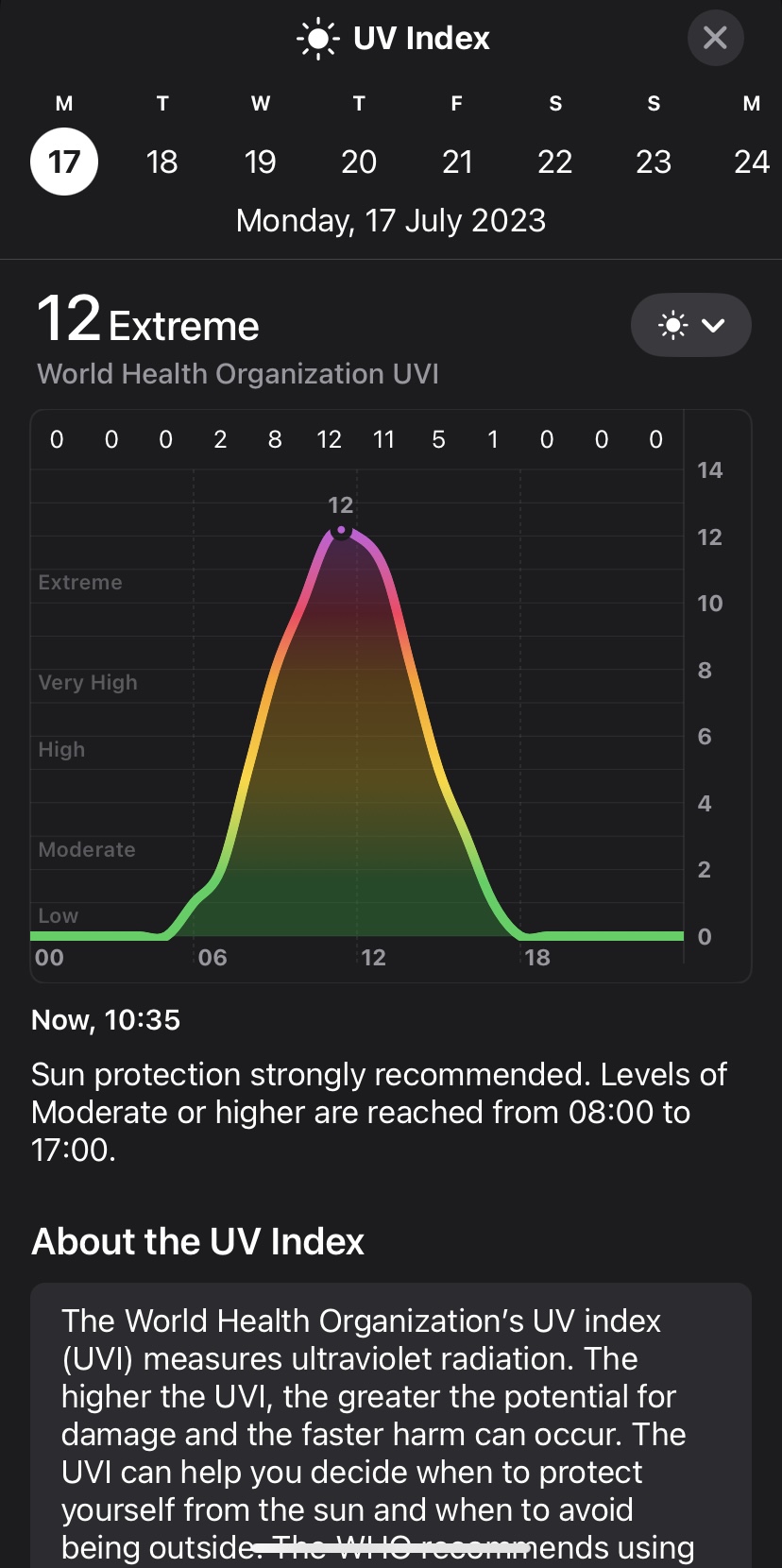

On my way to meet my friend I check the temperature on my phone. It’s still early in the morning but the sun is already so hot. It’s 33ºC but feels like 35ºC. The UV index is very high. This makes me worry, as I remember I forgot to put my face sunscreen on this morning when rushing out of my apartment. Going out on a hot day like this in a polluted city like Tehran is suicidal for the skin. It feels like I am already burning. The dryness of the air makes my skin feel so tight.

10 am

As I try to seek refuge in the shade of a tall glass building, I walk past a coffee shop where two middle-aged women with no headscarves on are sitting by the window. When they see me they show me a victory sign. I respond with a smile. Walking toward the main square, I notice a few police patrols driving slowly around the square. I hear myself breathing noisily.

A middle-aged man holding a freshly baked bread walks toward me, slows down his steps and whispers, “well done, I am with you.”

10.15 am

There she is, my friend Raha in a lovely colorful outfit with her scarf hanging over her shoulders. We hug. She compliments my hairstyle and I compliment hers. There is nothing special about our hairstyles but it’s actually the first time we see each other’s hair not covered, on the streets of Tehran. The absurdity of this makes us both laugh.

Raha tells me how she almost couldn’t catch her train because there were hijab officers at the metro station preventing veilless women from entering the metro. “But women without the compulsory hijab were more,” she says, “and many of us managed to pass the turnstiles,” she continues with a victorious tone in her voice.

10.30 am

We enter the coffee shop. There is a nice upbeat music being played. Raha takes out her phone to shazam it when all of a sudden the barista approaches her and says, “I am really sorry, but taking pictures or videos is prohibited here.” Raha puts her phone back into her pocket and tells him that she was only trying to find the song. The barista smiles apologetically and says, “Oh, in that case there is no problem. It’s just that the authorities have closed this place down twice in the past two months for serving hijab-less women. We can’t afford it to be closed again. We might go bankrupt next time they close this place. We are with you obviously and are happy to serve women like you. So we just ask our customers not to share photos of this place on social media so they won’t spot us easily.” We assure him we won’t share any photos on social media.

While sipping our tasty cold brew coffee, Raha and I talk about women, civil disobedience and how the city’s face has changed. She tells me about a few friends of hers that have received text messages saying they have been spotted in different locations without hijab and they have been fined. A friend of hers who was not covering her hair while driving has had her car impounded for a week.

11.30 am

As we leave the coffee shop and walk toward the square I notice the police patrols have now parked. There are groups of policewomen wearing long black chadors standing all over the square in strategic positions.

There is a stillness in the air.

“These are the hijab officers,” I tell Raha.

“Ignore them. Let’s simply pretend they are not there,” she says with a hesitant voice.

We cross the square and walk past the morality police officers. I become aware of my right hand moving slowly towards my headscarf over my shoulders to put it on my hair. My left hand literally holds my right hand to prevent it from touching the scarf.

My hands are clung together now.

Around us there are young girls and women not wearing hijab, some of them in short sleeves. Many of them don’t even pay attention to the police officers. Some have their headphones in their ears and pretend they don’t hear them. Others just rush pretending they are in a hurry. Some of these women are stopped by the police, but most of them are just being stared at by the officers as thoughthey are being challenged.

They don’t stop us.

“This is so heartening”, Raha says, “seeing all these veilless women and their fearlessness is encouraging. We are so many. They can’t stop all of us.”

“That’s true. We read and reflect a lot on feminism, sisterhood and solidarity, but I feel like this civil disobedience is an action on the field. It’s where theory and lived experience weave together. This is the space where we become changeagents.”

My hands are now relaxed hanging on the sides of my body.

“You know, it’s crazy how we involuntarily move our hands in the direction of our head to adjust the headscarf. It has grown on us. It has been a part of our daily urban experience since forever,” I say.

“We have done it all our lives that it is somehow incorporated into our body language,” Raha replies. “Well, we can still make use of this body language, but only to touch and adjust our hair,” she adds with a short laugh. “Yes, I think with all the sweat, my hair really needs to be neatened up right now,” I say, as we walk down the street under the boiling sun and toward the stationary shop.

It almost feels like my skin is on fire, as if I have a fever. How could I forget the sunscreen? The UV index is now extreme. I wish I had something to protect me from the glare of the sun.

I put my headscarf on when I get into the car. The car trip is only a few minutes, I think, trying to convince myself. If I remove my scarf and the driver asks me to put it back on, I might get into an argument with him, then I would cancel my ride and would have to request another one, so I would be late for my appointment. I’ve heard of some cases where drivers in order to avoid being fined, have rejected the ride if the passenger was not wearing hijab.

To distract myself, I check the news on my phone. But the first headline I read is like a slap in the face. The Morality Police is back on the streets with their full force. Well, they have been there all this time during the past ten months, I think to myself. But not like this, not this evident. I feel a throbbing pain in my head. I am so angry that I remove my headscarf in a sudden and jerky movement. The driver looks at me from the rear view mirror. I look him daringly in the eyes, waiting for him to tell me something in regard. He doesn’t say anything maybe because he knows in a few seconds we arrive at my destination. The post office is busy. Almost half of the women are not wearing hijab. The staff doesn’t make any problem except for one of them who seems to be really annoyed by having to serve bareheaded ladies! I look around to see if there are any security cameras and wonder if the head of this office hands the footage to the authorities if they are asked to. I have read that government offices are ordered not to provide services to women who don’t cover their hair.

Fortunately, the person serving me is nice and polite.

9.45 am

On my way to meet my friend I check the temperature on my phone. It’s still early in the morning but the sun is already so hot. It’s 33ºC but feels like 35ºC. The UV index is very high. This makes me worry, as I remember I forgot to put my face sunscreen on this morning when rushing out of my apartment. Going out on a hot day like this in a polluted city like Tehran is suicidal for the skin. It feels like I am already burning. The dryness of the air makes my skin feel so tight.

10 am

As I try to seek refuge in the shade of a tall glass building, I walk past a coffee shop where two middle-aged women with no headscarves on are sitting by the window. When they see me they show me a victory sign. I respond with a smile. Walking toward the main square, I notice a few police patrols driving slowly around the square. I hear myself breathing noisily.

A middle-aged man holding a freshly baked bread walks toward me, slows down his steps and whispers, “well done, I am with you.”

10.15 am

There she is, my friend Raha in a lovely colorful outfit with her scarf hanging over her shoulders. We hug. She compliments my hairstyle and I compliment hers. There is nothing special about our hairstyles but it’s actually the first time we see each other’s hair not covered, on the streets of Tehran. The absurdity of this makes us both laugh.

Raha tells me how she almost couldn’t catch her train because there were hijab officers at the metro station preventing veilless women from entering the metro. “But women without the compulsory hijab were more,” she says, “and many of us managed to pass the turnstiles,” she continues with a victorious tone in her voice.

10.30 am

We enter the coffee shop. There is a nice upbeat music being played. Raha takes out her phone to shazam it when all of a sudden the barista approaches her and says, “I am really sorry, but taking pictures or videos is prohibited here.” Raha puts her phone back into her pocket and tells him that she was only trying to find the song. The barista smiles apologetically and says, “Oh, in that case there is no problem. It’s just that the authorities have closed this place down twice in the past two months for serving hijab-less women. We can’t afford it to be closed again. We might go bankrupt next time they close this place. We are with you obviously and are happy to serve women like you. So we just ask our customers not to share photos of this place on social media so they won’t spot us easily.” We assure him we won’t share any photos on social media.

While sipping our tasty cold brew coffee, Raha and I talk about women, civil disobedience and how the city’s face has changed. She tells me about a few friends of hers that have received text messages saying they have been spotted in different locations without hijab and they have been fined. A friend of hers who was not covering her hair while driving has had her car impounded for a week.

11.30 am

As we leave the coffee shop and walk toward the square I notice the police patrols have now parked. There are groups of policewomen wearing long black chadors standing all over the square in strategic positions.

There is a stillness in the air.

“These are the hijab officers,” I tell Raha.

“Ignore them. Let’s simply pretend they are not there,” she says with a hesitant voice.

We cross the square and walk past the morality police officers. I become aware of my right hand moving slowly towards my headscarf over my shoulders to put it on my hair. My left hand literally holds my right hand to prevent it from touching the scarf.

My hands are clung together now.

Around us there are young girls and women not wearing hijab, some of them in short sleeves. Many of them don’t even pay attention to the police officers. Some have their headphones in their ears and pretend they don’t hear them. Others just rush pretending they are in a hurry. Some of these women are stopped by the police, but most of them are just being stared at by the officers as thoughthey are being challenged.

They don’t stop us.

“This is so heartening”, Raha says, “seeing all these veilless women and their fearlessness is encouraging. We are so many. They can’t stop all of us.”

“That’s true. We read and reflect a lot on feminism, sisterhood and solidarity, but I feel like this civil disobedience is an action on the field. It’s where theory and lived experience weave together. This is the space where we become changeagents.”

My hands are now relaxed hanging on the sides of my body.

“You know, it’s crazy how we involuntarily move our hands in the direction of our head to adjust the headscarf. It has grown on us. It has been a part of our daily urban experience since forever,” I say.

“We have done it all our lives that it is somehow incorporated into our body language,” Raha replies. “Well, we can still make use of this body language, but only to touch and adjust our hair,” she adds with a short laugh. “Yes, I think with all the sweat, my hair really needs to be neatened up right now,” I say, as we walk down the street under the boiling sun and toward the stationary shop.

It almost feels like my skin is on fire, as if I have a fever. How could I forget the sunscreen? The UV index is now extreme. I wish I had something to protect me from the glare of the sun.

UV index in Tehran. Courtesy the author

12 pm

The air inside the stationary shop is cool. It smells like paper and ink and childhood memories. This is a family owned shop we used to go to as school girls. “I noticed something strange,” Raha says as soon as we leave the shop, “the father and son who run this stationery shop used to be angry every time I came here. They were never in a good mood. But they were really nice with us today.” “Hmm, that’s true. Maybe it’s because we are not wearing the veil.” The idea of how city dwellers’ mood changes when they see women defying the mandatory hijab makes us both happy. We talk for a while longer about it before saying goodbye and taking our separate ways.

1 pm

On my way back home I remember I needed to buy milk. The taxi driver drops me off at the mall. My skin cools down a bit when I enter the air-conditioned mall.

Almost all the women at the mall are veilless.

My phone has almost run out of battery because of the heat. So I cannot access the cab application. I ask the mall’s security guard if he can call me a taxi. He looks at my hair and refuses to answer. When I repeat the question, he tells me he doesn’t have a phone. I feel like he hesitates to talk to me either because of the security cameras or because he is really bothered by seeing a hijab-less woman. In either case his attitude annoys me so much that I prefer to leave the mall. Just like many men and women who decide to boycott shops or restaurants who don’t serve veilless women or who treat them poorly.

I wait outside trying to find a taxi. There is none.

With the remaining battery on my phone I try to google the phone number of a few taxi companies nearby. I call a couple of them. The first one says there is no car available at the moment. The other one tells me the wait is more than 20 minutes.

It is lunch time and the heat is unbearable. The street is deserted. I check my phone to see the temperature but it has completely gone dead now!

1.30 pm

I feel like I have waited enough. I really need to get going. Waiting for a taxi to appear, seems like nonsense under this heat.

The moment I decide to move, I see a taxi coming my way. It stops. What a miracle, I think.

As I am enjoying the cool breeze in the car, the taxi driver looks at me from the mirror and says “Miss, please put on your headscarf!”

“I am not going to. Pull over, I am getting out.”

Here I am, under the blazing sun on a deserted street again.

My phone is dead but I am sure the temperature is above 34ºC. And the UV index is definitely as high as it can get.

I walk past a shop that sells sun hats and caps. I stop for a moment and try on a hat. The shopkeeper tries to sell it to me saying it’s a must have on days like today. I take a look at myself in the mirror and say “true, but then it would seem like I have put it on to cover my hair. I don’t want to cover my hair at any cost.” He smiles and says, “woman, life, freedom.”

I say, “woman, life, freedom.”

I am walking under the sun on a hot afternoon in July, with no hat, no headscarf and no sunscreen, but I don’t care about the heat anymore. I am happy and hopeful.

The air inside the stationary shop is cool. It smells like paper and ink and childhood memories. This is a family owned shop we used to go to as school girls. “I noticed something strange,” Raha says as soon as we leave the shop, “the father and son who run this stationery shop used to be angry every time I came here. They were never in a good mood. But they were really nice with us today.” “Hmm, that’s true. Maybe it’s because we are not wearing the veil.” The idea of how city dwellers’ mood changes when they see women defying the mandatory hijab makes us both happy. We talk for a while longer about it before saying goodbye and taking our separate ways.

1 pm

On my way back home I remember I needed to buy milk. The taxi driver drops me off at the mall. My skin cools down a bit when I enter the air-conditioned mall.

Almost all the women at the mall are veilless.

My phone has almost run out of battery because of the heat. So I cannot access the cab application. I ask the mall’s security guard if he can call me a taxi. He looks at my hair and refuses to answer. When I repeat the question, he tells me he doesn’t have a phone. I feel like he hesitates to talk to me either because of the security cameras or because he is really bothered by seeing a hijab-less woman. In either case his attitude annoys me so much that I prefer to leave the mall. Just like many men and women who decide to boycott shops or restaurants who don’t serve veilless women or who treat them poorly.

I wait outside trying to find a taxi. There is none.

With the remaining battery on my phone I try to google the phone number of a few taxi companies nearby. I call a couple of them. The first one says there is no car available at the moment. The other one tells me the wait is more than 20 minutes.

It is lunch time and the heat is unbearable. The street is deserted. I check my phone to see the temperature but it has completely gone dead now!

1.30 pm

I feel like I have waited enough. I really need to get going. Waiting for a taxi to appear, seems like nonsense under this heat.

The moment I decide to move, I see a taxi coming my way. It stops. What a miracle, I think.

As I am enjoying the cool breeze in the car, the taxi driver looks at me from the mirror and says “Miss, please put on your headscarf!”

“I am not going to. Pull over, I am getting out.”

Here I am, under the blazing sun on a deserted street again.

My phone is dead but I am sure the temperature is above 34ºC. And the UV index is definitely as high as it can get.

I walk past a shop that sells sun hats and caps. I stop for a moment and try on a hat. The shopkeeper tries to sell it to me saying it’s a must have on days like today. I take a look at myself in the mirror and say “true, but then it would seem like I have put it on to cover my hair. I don’t want to cover my hair at any cost.” He smiles and says, “woman, life, freedom.”

I say, “woman, life, freedom.”

I am walking under the sun on a hot afternoon in July, with no hat, no headscarf and no sunscreen, but I don’t care about the heat anymore. I am happy and hopeful.

anonymous is a practitioner from Tehran, Iran.