Chen Di: Cyclone Complex – On Messy Credit and Foiled Realities, Sanjita Majumder

September 2024

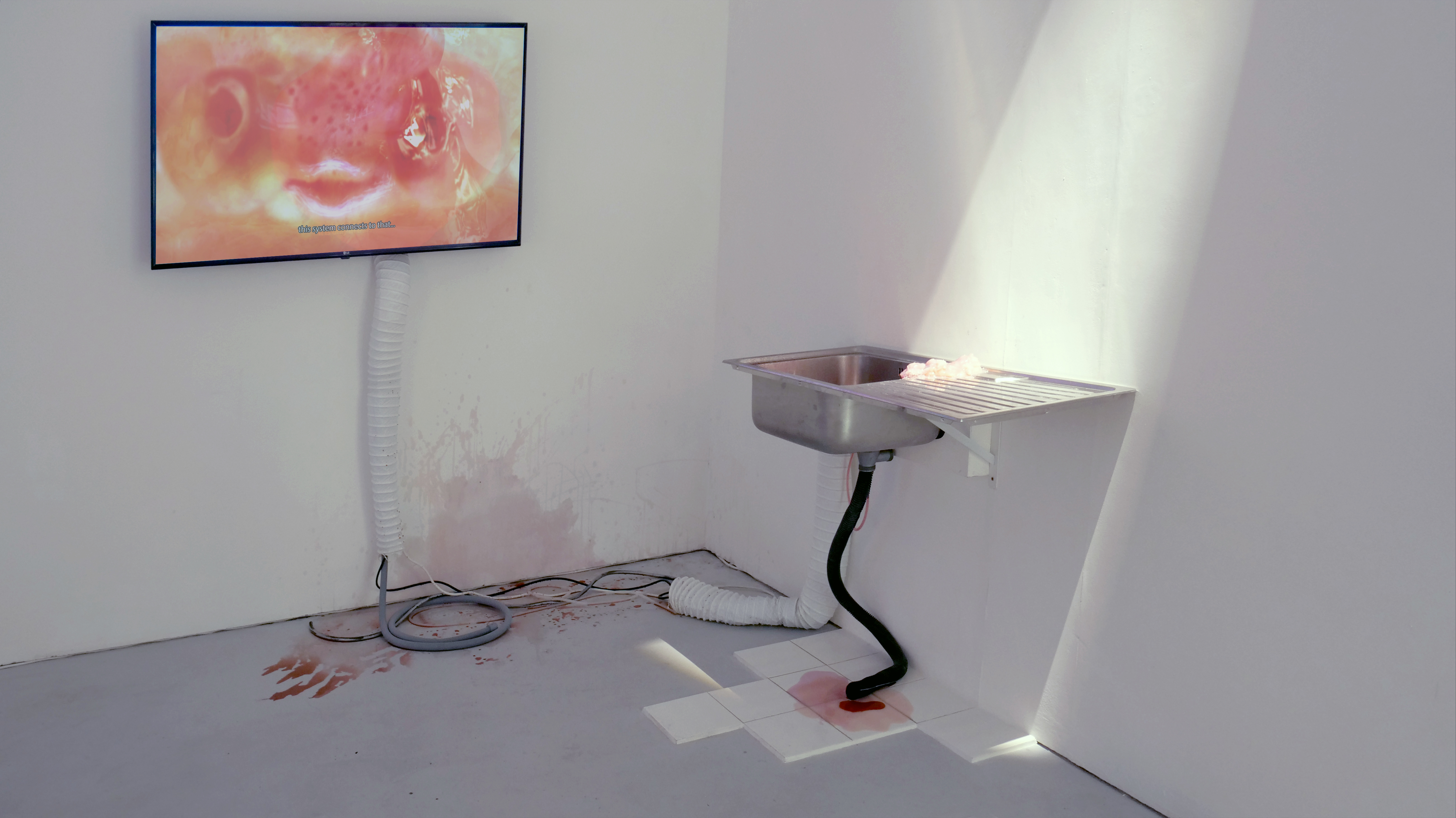

Chen Di, Fortune Weight, 2024, installation view. Photo courtesy the artist

Chen Di, Fortune Weight, 2024, installation view. Photo courtesy the artist

Inside a humming sonic sphere woven by bird and insect noise, the audience of Chen Di’s recent video installation find themselves hovering a a curious gathering. There is a newly painted, pseudo-classical Chinese pavilion in the artist’s hometown and four older women. We witness intensifying signs of an upcoming storm seemingly summoned by the women through speech and ritual.

The group takes turns to blow into a pile of burning charcoal with a miniature teapot on top, reciting a series of numbers that vaguely resemble real-time updates of some sort of chance fluctuations. The characters neither comply with the commonly assumed shape of sci-fi characters nor the visual features associated with forms of ‘exotic magic’. These ‘aunts’ are seen in their puffy winter coats and cartoon-printed gloves, as if they were caught on their way to a local market on an ordinary afternoon. And yet, I felt a sense of uncanny chill when the muffled stormy thunder crept closer and suddenly swept over the immersive soundscape, following a powerful blow of air delivered by one aunt into the smouldering ashes. In Fortune Weight (2024), Chen adapts her long-practiced attention to the relations between image and sound, movement and animacy, to transform a plain and disenchanted urban public space in her own semi-tropical coastal hometown into a site of something ineffable – a momentary centre of what she calls ‘financial/magical operations’ to a significant node in a network that holds the potential of striking out across a wider scale of complex systems charged with risk and fortune.

The methods of world-building or storytelling in Chen’s work are eccentric: there are hardly any birds-eye or panoramic views of the ‘event’ or of the land under its influence, nor is there any commentary guiding the viewer towards a neatly coherent narrative. Filmed with a gimbal or camera stabiliser, the image on the screen tilts at odd angles and quietly slides around the scene. The camera reverses and retreats behind bushes and occasionally peeks from a distance. The camera is restless. It keeps hiding, through which its presence is constantly called to attention. We see fragments of visual hints accompanied by densely overlapping soundscapes: fog rising, the sky darkening and branches trembling, and in the next moment, we are immediately dragged closely towards each character’s zoomed-in face as everything on the screen starts to jerk and oscillate like a fly against a glass window before the film cuts to a completely different scene in a brightly lit scientific lab. Chen's choices here – of restraining from any apparent ‘effects’ in supernatural or science-fictional worlding, and instead focusing on building a constantly intensifying acoustic soundscape – challenge the conventional norms of storytelling in moving image work and instead create an intensive sense bubbling with ambiguity and suspension. Until the end of the film, very little is revealed about the nature of the ritual or the exact mechanism of the connections between the aunts’ operations and the apparent cyclone.

The title of the work, Fortune Weight, functions as an ambiguous handle that leads one’s mind between heterogenous imagery and ideas. We see one of the conductors of the ritual, the artist’s mother in real life, filming herself staring at the camera, spinning and sliding around on a swivel chair in a medical or scientific lab, traversing the limited space while slowly and intently nibbling on a mung bean cake. Past the level of the absurd humour of the scene, a complex network emerges the more one sits with the work: an interplay between ideas like the feedback loops of natural catastrophe and of global power structures, between financial speculation and religious future-telling, between kinship groups and credit systems, as well as risk management played off against the collective creation of hope. The tilted, sliding, and oscillated image from the semi-fictional world on screen appears as a curious contradiction and refraction to its corresponding reality, challenging and complicating the boundaries between prediction, simulation, and realities across varied modes of being and believing.

As the second episode of the artist’s ongoing trilogy, Fortune Weight (2024), presented as a single-channel video installation, was part of comms, a group exhibition at SET Woolwich in May 2024, among other works by artists Akinsola Lawanson, James Raphael Tabbush, and Jelena Viskovic. It was also part of the Conditions Program’s Film and Video Screening event at ICA, London, on 31st July 2024. This text and conversation is in reference to the latest edit of the work, in August 2024.

Sanjita Majumder: In your most recent film, Fortune Weight (2024), the people on screen converse about buying financial luck through Buddhist temples, seemingly casting a spell to bring a typhoon. How did you start drawing connections between these ideas – finance, religion, magic and weather systems? And how did these ideas connect to the setting you chose for the film?

Chen Di: Those ideas like finance, belief systems, magic/techniques, and weather control, as well as the complex ways through which they are somehow connected to each other, have all been threads in and material for my current research. When it comes to the starting point of a new work, it has always been something rather small and specific, something that grows more directly from my personal experiences. At the beginning of this year, I went back to my home city in Fujian, Southeast China. It is located in a coastal area with mountains on one side and the sea full of fish farms on the other. While visiting my family and wandering around eavesdropping in the city, observing how elderly people entertain themselves in public, I started to draw connections between things I saw and these more abstract ideas. There were so many complex layers and textures in the daily activities of local life that I could play with.

One thing that interested me during that visit was something that could be translated as ‘mutual aid groups’. It is a form of self-organised private loan association among colleagues, friends and relatives where money is gathered and loaned through bidding meetings. There are theories about its earliest appearance in history, some of them dated back to around 300 AD in the Jin Dynasty. It is still widely existent in Hokkien-speaking areas in China and Taiwan, seemingly with decreasing popularity because of the development of e-finance tools and micro-credit. It is also currently illegal in China to form and take part in mutual aid groups. I remember incidents of local financial crises being partly due to debts being passed along and expanded across the networks of mutual aid associations around a decade ago. A dominant part of how the mutual aid associations function is through personal connections, where people evaluate the risks and form approximate credit systems based on the assessment of how deeply the given individuals are embedded in the local society and the possibilities of them escaping this network of mutual responsibilities, resources and distributed risk. So at some point this scene came up as an image, where deities in the form of elderly local ladies gather around on the mountainside, gambling over an upcoming typhoon. With this scene in mind, I liked the idea of them looking somehow similar to one another. That’s when I decided to invite my aunts to be the deities.

The question of mutual aid or credit systems, which have kind of evolved around kinship and non-nuclear families, is interesting and seems very specific to a social and cultural fabric in Southeast Asia. As you suggested, it brings up aspects of both freedom and control. When we think of this balance of risk in the work, we're bringing together three very disparate things: the economic system, an almost metaphysical kind of religious fortune-based practice, and then systems of climate such as typhoons, in order to see the larger interconnectivities between all of these, is that right?

Yes, the idea of typhoon came up partly because it has always been a constant presence in local life as I remember it – how the city has been designed, built and inhabited with the constant presence of strong wind, rapid rainstorms and potential flooding and landslides during typhoon season, from the traditional design of roof tiles to the layout of the city, including how the latest sale prices of a newly developed housing property was partly affected by the risk assessment on its resilience against different levels of typhoon or other similar natural disasters. So there is this idea of a disaster that happens regularly, is to certain extents predictable, and could even be somehow harvested and transformed into a profitable set of information which people can bid upon. I was also very interested in the idea of attempts at controlling, or the idea of gambling with, something that seems to be so much bigger than the perception of an individual human.

That's super interesting. It reminds me a bit of Amitav Ghosh's book on cyclones in India, The Great Derangement, in that these kinds of natural catastrophes are not yet very common in the West, but they're very, very common in South Asia. This kind of system which is built around these natural catastrophes, is so specific to those regions which are already kind of always in that state of cyclical crises occurring because of cyclones or typhoons. This kind of building of a system that addresses that risk perhaps is also a cultural way of tackling that risk, in a way saying that the risk is something that is a part of our life and hence incorporated in life rather than kind of looked at with dread or paralysis.

Yes, perhaps these complex systemic risks act as a constant foil which societies build up both mental and physical structures against and around.

The group takes turns to blow into a pile of burning charcoal with a miniature teapot on top, reciting a series of numbers that vaguely resemble real-time updates of some sort of chance fluctuations. The characters neither comply with the commonly assumed shape of sci-fi characters nor the visual features associated with forms of ‘exotic magic’. These ‘aunts’ are seen in their puffy winter coats and cartoon-printed gloves, as if they were caught on their way to a local market on an ordinary afternoon. And yet, I felt a sense of uncanny chill when the muffled stormy thunder crept closer and suddenly swept over the immersive soundscape, following a powerful blow of air delivered by one aunt into the smouldering ashes. In Fortune Weight (2024), Chen adapts her long-practiced attention to the relations between image and sound, movement and animacy, to transform a plain and disenchanted urban public space in her own semi-tropical coastal hometown into a site of something ineffable – a momentary centre of what she calls ‘financial/magical operations’ to a significant node in a network that holds the potential of striking out across a wider scale of complex systems charged with risk and fortune.

The methods of world-building or storytelling in Chen’s work are eccentric: there are hardly any birds-eye or panoramic views of the ‘event’ or of the land under its influence, nor is there any commentary guiding the viewer towards a neatly coherent narrative. Filmed with a gimbal or camera stabiliser, the image on the screen tilts at odd angles and quietly slides around the scene. The camera reverses and retreats behind bushes and occasionally peeks from a distance. The camera is restless. It keeps hiding, through which its presence is constantly called to attention. We see fragments of visual hints accompanied by densely overlapping soundscapes: fog rising, the sky darkening and branches trembling, and in the next moment, we are immediately dragged closely towards each character’s zoomed-in face as everything on the screen starts to jerk and oscillate like a fly against a glass window before the film cuts to a completely different scene in a brightly lit scientific lab. Chen's choices here – of restraining from any apparent ‘effects’ in supernatural or science-fictional worlding, and instead focusing on building a constantly intensifying acoustic soundscape – challenge the conventional norms of storytelling in moving image work and instead create an intensive sense bubbling with ambiguity and suspension. Until the end of the film, very little is revealed about the nature of the ritual or the exact mechanism of the connections between the aunts’ operations and the apparent cyclone.

The title of the work, Fortune Weight, functions as an ambiguous handle that leads one’s mind between heterogenous imagery and ideas. We see one of the conductors of the ritual, the artist’s mother in real life, filming herself staring at the camera, spinning and sliding around on a swivel chair in a medical or scientific lab, traversing the limited space while slowly and intently nibbling on a mung bean cake. Past the level of the absurd humour of the scene, a complex network emerges the more one sits with the work: an interplay between ideas like the feedback loops of natural catastrophe and of global power structures, between financial speculation and religious future-telling, between kinship groups and credit systems, as well as risk management played off against the collective creation of hope. The tilted, sliding, and oscillated image from the semi-fictional world on screen appears as a curious contradiction and refraction to its corresponding reality, challenging and complicating the boundaries between prediction, simulation, and realities across varied modes of being and believing.

As the second episode of the artist’s ongoing trilogy, Fortune Weight (2024), presented as a single-channel video installation, was part of comms, a group exhibition at SET Woolwich in May 2024, among other works by artists Akinsola Lawanson, James Raphael Tabbush, and Jelena Viskovic. It was also part of the Conditions Program’s Film and Video Screening event at ICA, London, on 31st July 2024. This text and conversation is in reference to the latest edit of the work, in August 2024.

Sanjita Majumder: In your most recent film, Fortune Weight (2024), the people on screen converse about buying financial luck through Buddhist temples, seemingly casting a spell to bring a typhoon. How did you start drawing connections between these ideas – finance, religion, magic and weather systems? And how did these ideas connect to the setting you chose for the film?

Chen Di: Those ideas like finance, belief systems, magic/techniques, and weather control, as well as the complex ways through which they are somehow connected to each other, have all been threads in and material for my current research. When it comes to the starting point of a new work, it has always been something rather small and specific, something that grows more directly from my personal experiences. At the beginning of this year, I went back to my home city in Fujian, Southeast China. It is located in a coastal area with mountains on one side and the sea full of fish farms on the other. While visiting my family and wandering around eavesdropping in the city, observing how elderly people entertain themselves in public, I started to draw connections between things I saw and these more abstract ideas. There were so many complex layers and textures in the daily activities of local life that I could play with.

One thing that interested me during that visit was something that could be translated as ‘mutual aid groups’. It is a form of self-organised private loan association among colleagues, friends and relatives where money is gathered and loaned through bidding meetings. There are theories about its earliest appearance in history, some of them dated back to around 300 AD in the Jin Dynasty. It is still widely existent in Hokkien-speaking areas in China and Taiwan, seemingly with decreasing popularity because of the development of e-finance tools and micro-credit. It is also currently illegal in China to form and take part in mutual aid groups. I remember incidents of local financial crises being partly due to debts being passed along and expanded across the networks of mutual aid associations around a decade ago. A dominant part of how the mutual aid associations function is through personal connections, where people evaluate the risks and form approximate credit systems based on the assessment of how deeply the given individuals are embedded in the local society and the possibilities of them escaping this network of mutual responsibilities, resources and distributed risk. So at some point this scene came up as an image, where deities in the form of elderly local ladies gather around on the mountainside, gambling over an upcoming typhoon. With this scene in mind, I liked the idea of them looking somehow similar to one another. That’s when I decided to invite my aunts to be the deities.

The question of mutual aid or credit systems, which have kind of evolved around kinship and non-nuclear families, is interesting and seems very specific to a social and cultural fabric in Southeast Asia. As you suggested, it brings up aspects of both freedom and control. When we think of this balance of risk in the work, we're bringing together three very disparate things: the economic system, an almost metaphysical kind of religious fortune-based practice, and then systems of climate such as typhoons, in order to see the larger interconnectivities between all of these, is that right?

Yes, the idea of typhoon came up partly because it has always been a constant presence in local life as I remember it – how the city has been designed, built and inhabited with the constant presence of strong wind, rapid rainstorms and potential flooding and landslides during typhoon season, from the traditional design of roof tiles to the layout of the city, including how the latest sale prices of a newly developed housing property was partly affected by the risk assessment on its resilience against different levels of typhoon or other similar natural disasters. So there is this idea of a disaster that happens regularly, is to certain extents predictable, and could even be somehow harvested and transformed into a profitable set of information which people can bid upon. I was also very interested in the idea of attempts at controlling, or the idea of gambling with, something that seems to be so much bigger than the perception of an individual human.

That's super interesting. It reminds me a bit of Amitav Ghosh's book on cyclones in India, The Great Derangement, in that these kinds of natural catastrophes are not yet very common in the West, but they're very, very common in South Asia. This kind of system which is built around these natural catastrophes, is so specific to those regions which are already kind of always in that state of cyclical crises occurring because of cyclones or typhoons. This kind of building of a system that addresses that risk perhaps is also a cultural way of tackling that risk, in a way saying that the risk is something that is a part of our life and hence incorporated in life rather than kind of looked at with dread or paralysis.

Yes, perhaps these complex systemic risks act as a constant foil which societies build up both mental and physical structures against and around.

Chen Di, Ever Since I Lost My AddOn, I Saw Her Everywhere, 2023, installation view. Photo courtesy the artist

Looking for a through-line within the last few years of your practice, but even going further back, I notice a refusal to take the camera, or simply the imagined viewpoint of the image, for granted. The image often moves in ways that destabilise assumptions, such as the restless vibration of the image of the characters towards the end of the most recent film. Could you talk about where this comes from? Is it more about the tropes of filmmaking, about questioning the subjectivity behind the image, or something else entirely?

When it comes to image-making, I have always been interested in something that's beyond the static and visible. And when it comes to operating a (sometimes virtual) camera and making a moving image piece, I always found building through the visible clues towards the invisible, towards something behind the image, more fascinating than working merely with what one can see.

I really enjoy moments when the camera somehow starts to hint at a certain level of agency within itself. I like moments when it feels like you can't tell what it is that is looking at this image that you are looking at, or the image you encounter is somehow an obscure surface, a false reflection, or a doppelgänger, like some sort of foil, of its corresponding ‘reality’.

This kind of ambiguity of the state of the ‘eye’ is always there in my videos. In the first episode of my trilogy, Ever Since I Lost My AddOn, I Saw Her Everywhere (ESILMAISHE) (2023), I also tried to complicate the texture of the image by adding CGI – sometimes layering animation or visual effects on top of the filmed materials. In this ongoing episode, Fortune Weight, I plan to continue using CGI but push it in a more photorealistic or subtle way compared to the slightly more post-internet flavour that was in ESILMAISHE. I hope the aesthetic or visual associations will remain in more or less an ambiguous state, and that this will provoke some kind of confusion, doubts or complex feelings in people who see it.

On the one hand, what you depict is a very culturally specific ritual, a deep audience with otherness, and your camera’s movement around it almost gives this quality of seer or some kind of fortune telling in itself. So I think that that movement works very well to draw that out. But you also seem to be interested in a movement away from static images towards a particular way of constructing images that are also not conventionally, you know, the slow pans and the trolley track shots of documentary or cinema. How much of this narrative or this artwork demanded that you work from that perspective of this force or presence, and how much is your concern with the practice of moving image today?

I'm very interested in the kind of messiness or complexity, or the visual textures in local cultural practices, but I also wanted it to move slightly away from the specificity of a particular group of people, or a particular location. I noticed that, when it comes to certain themes, such as artists going to a place where the local cultural activities are less represented in a sort of Global North contemporary art context, moving image works tend to take up similar documentary formats. One of the common visual languages for this kind of work would be this tasteful cinematic or ethnographic aesthetic that we sometimes see in institutions or galleries now. I feel that this approach somehow settles very smoothly into a particular norm that the funding or prize systems reward and that standard image-making devices afford. Looking at these works’ formal aspects, it is often not as radical as what the works are claiming to do politically. I found this gap interesting – how the political statement of the work is about resistance or trying to draw attention to create a world of many centres, yet the format of the work comfortably sits within a homogeneity of industrial production norms. I might appear to be slightly old-fashioned or naive in this sense but I am still interested in a certain amount of formal visual critique, to think through how my images are made and communicated to individuals, and I still think this could be a very crucial site for some sort of resistance. That's partly where the kind of monstrosity or alien-ness of the image comes from.

Your last two films were based around footage shot in your hometown, with family members as main protagonists. Would you characterise these strategies as related to literary autofiction, in which you play with the boundaries of fiction and fact, including your own identity as artist? Is this the 'real world' we are being shown, are these your 'real family', and how would you characterise your own role or positionality in these works?

I did not intend to make a work of autofiction, at least not consciously. I started to work with my family at home in the first episode of the trilogy, ESILMAISHE, partly because I always wanted to make a sci-fi film that’s vaguely about, or set in, a fish farm. When it comes to scripting, and hosting filming sessions, it was normally a collective process – I would give a general idea or story and explain what kind of images I might want to capture, and then just film my family doing what they understood as the ideas, or sometimes just their daily activities and conversations. When editing I tried to pick useful moments from the footage and sometimes twisted them into different groups of ideas or story blocks I had in mind. Sometimes the story went in a completely unexpected direction, and I enjoyed those moments too. On the idea of fictioning, I found a lot of local cultural activities, language or phenomena a rich source of inspiration, however, I feel like the level of ‘fictionalisation’ is very closely related to how much vulnerability I wanted to show in this work.

I'm also thinking that when we make films with people who are intimate with us, we ourselves know that they are family, but when it's screened in exhibition spaces or something, the footage doesn't spell this out. So when you come back to your studio and you're working with all that footage, it's as if you still carry part of them and their meanings with you while transforming them into something else. Also this boundary between the personal and public sphere is a political and particularly a feminist issue that can be foregrounded here. I think this would be a good space to kind of bring those things together and address these questions about how you attempted to capture your relatives in their everyday setting and activities, but you also look at this event as an outsider because you are now an immigrant artist.

Sometimes I have mixed feelings when it comes to making some sort of fictionalised version of certain scenes. Sometimes I even have something close to a sense of embarrassment when I work on the footage. On the one hand there is this sort of raw, non-radical details from the daily life of a rural small city in China, within its sometimes problematic systems which I grew up trying to escape from; on the other hand I have the chance to play with these materials and create some sort of a counter-reality which sort of stands on its own as an alternative ‘centre’ outside of the more dominant cultural and geopolitical ‘centres’, where some sort of fictionalised societal models might be created and unfolded in a game/simulation with my family and where the images take on a life of their own.

When it comes to image-making, I have always been interested in something that's beyond the static and visible. And when it comes to operating a (sometimes virtual) camera and making a moving image piece, I always found building through the visible clues towards the invisible, towards something behind the image, more fascinating than working merely with what one can see.

I really enjoy moments when the camera somehow starts to hint at a certain level of agency within itself. I like moments when it feels like you can't tell what it is that is looking at this image that you are looking at, or the image you encounter is somehow an obscure surface, a false reflection, or a doppelgänger, like some sort of foil, of its corresponding ‘reality’.

This kind of ambiguity of the state of the ‘eye’ is always there in my videos. In the first episode of my trilogy, Ever Since I Lost My AddOn, I Saw Her Everywhere (ESILMAISHE) (2023), I also tried to complicate the texture of the image by adding CGI – sometimes layering animation or visual effects on top of the filmed materials. In this ongoing episode, Fortune Weight, I plan to continue using CGI but push it in a more photorealistic or subtle way compared to the slightly more post-internet flavour that was in ESILMAISHE. I hope the aesthetic or visual associations will remain in more or less an ambiguous state, and that this will provoke some kind of confusion, doubts or complex feelings in people who see it.

On the one hand, what you depict is a very culturally specific ritual, a deep audience with otherness, and your camera’s movement around it almost gives this quality of seer or some kind of fortune telling in itself. So I think that that movement works very well to draw that out. But you also seem to be interested in a movement away from static images towards a particular way of constructing images that are also not conventionally, you know, the slow pans and the trolley track shots of documentary or cinema. How much of this narrative or this artwork demanded that you work from that perspective of this force or presence, and how much is your concern with the practice of moving image today?

I'm very interested in the kind of messiness or complexity, or the visual textures in local cultural practices, but I also wanted it to move slightly away from the specificity of a particular group of people, or a particular location. I noticed that, when it comes to certain themes, such as artists going to a place where the local cultural activities are less represented in a sort of Global North contemporary art context, moving image works tend to take up similar documentary formats. One of the common visual languages for this kind of work would be this tasteful cinematic or ethnographic aesthetic that we sometimes see in institutions or galleries now. I feel that this approach somehow settles very smoothly into a particular norm that the funding or prize systems reward and that standard image-making devices afford. Looking at these works’ formal aspects, it is often not as radical as what the works are claiming to do politically. I found this gap interesting – how the political statement of the work is about resistance or trying to draw attention to create a world of many centres, yet the format of the work comfortably sits within a homogeneity of industrial production norms. I might appear to be slightly old-fashioned or naive in this sense but I am still interested in a certain amount of formal visual critique, to think through how my images are made and communicated to individuals, and I still think this could be a very crucial site for some sort of resistance. That's partly where the kind of monstrosity or alien-ness of the image comes from.

Your last two films were based around footage shot in your hometown, with family members as main protagonists. Would you characterise these strategies as related to literary autofiction, in which you play with the boundaries of fiction and fact, including your own identity as artist? Is this the 'real world' we are being shown, are these your 'real family', and how would you characterise your own role or positionality in these works?

I did not intend to make a work of autofiction, at least not consciously. I started to work with my family at home in the first episode of the trilogy, ESILMAISHE, partly because I always wanted to make a sci-fi film that’s vaguely about, or set in, a fish farm. When it comes to scripting, and hosting filming sessions, it was normally a collective process – I would give a general idea or story and explain what kind of images I might want to capture, and then just film my family doing what they understood as the ideas, or sometimes just their daily activities and conversations. When editing I tried to pick useful moments from the footage and sometimes twisted them into different groups of ideas or story blocks I had in mind. Sometimes the story went in a completely unexpected direction, and I enjoyed those moments too. On the idea of fictioning, I found a lot of local cultural activities, language or phenomena a rich source of inspiration, however, I feel like the level of ‘fictionalisation’ is very closely related to how much vulnerability I wanted to show in this work.

I'm also thinking that when we make films with people who are intimate with us, we ourselves know that they are family, but when it's screened in exhibition spaces or something, the footage doesn't spell this out. So when you come back to your studio and you're working with all that footage, it's as if you still carry part of them and their meanings with you while transforming them into something else. Also this boundary between the personal and public sphere is a political and particularly a feminist issue that can be foregrounded here. I think this would be a good space to kind of bring those things together and address these questions about how you attempted to capture your relatives in their everyday setting and activities, but you also look at this event as an outsider because you are now an immigrant artist.

Sometimes I have mixed feelings when it comes to making some sort of fictionalised version of certain scenes. Sometimes I even have something close to a sense of embarrassment when I work on the footage. On the one hand there is this sort of raw, non-radical details from the daily life of a rural small city in China, within its sometimes problematic systems which I grew up trying to escape from; on the other hand I have the chance to play with these materials and create some sort of a counter-reality which sort of stands on its own as an alternative ‘centre’ outside of the more dominant cultural and geopolitical ‘centres’, where some sort of fictionalised societal models might be created and unfolded in a game/simulation with my family and where the images take on a life of their own.

Chen Di is an artist based in London. Chen’s practice combines speculative fictional documentaries, organic moving sculptures, digital games, and sound. Chen’s latest projects steal and transform ideas, methodologies, and stories from animism, finance, techniques of magic, agriculture and biotechnology industries, internet-oriented mass sociogenic bodily symptoms as well as Chen’s family gatherings. Chen’s work has been part of exhibitions and events in Mark Leckey’s monthly NTS show, London/NTS Radio, The Bomb Factory Art Foundation, London, Frappant Galerie, Hamburg, TANK Shanghai, and Space Ubermensch, Busan.

Sanjita Majumder, a writer and lecturer, specialises in film and media studies. She is a founding member at Counterfield Publication. Her writing has been featured across international newspapers and independent art & film studies publication. She holds a doctoral degree in Visual Cultures from Goldsmiths, University of London.

Sanjita Majumder, a writer and lecturer, specialises in film and media studies. She is a founding member at Counterfield Publication. Her writing has been featured across international newspapers and independent art & film studies publication. She holds a doctoral degree in Visual Cultures from Goldsmiths, University of London.